LS: finding william, finding myself

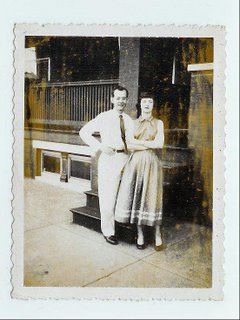

Photo left: Bill Ebauer and Joy Snider, Baltimore, MD, 1952.

My husband requested a crazy birthday present this past weekend. "Three hours of complain-free help in cleaning the house."

He'll be finishing up his MA in Theology this year and going on for a PhD so we've had some major shake-ups in household duties and fiscal responsibilities. In other words, I bring home most of the bacon and he fries it up in a pan.

My first thought? "Why didn't I think about a present like that when I was the one with those responsibilities?"

So the kids and I joined him at 9:30 on his birthday. We toted lots of books, shelved them, and some of us ended up down in the basement. The Wallers built our house in 1882; the basement is dirt, rich, dark dirt. I looked like I had been on the outskirts of a volcanic eruption when I was through.

My job? Go through a corner full of boxes; throw out what we didn't want to keep; and arrange the rest into plastic tubs. Most of the boxes held papers and pictures, keepsakes and cards from people I didn't know, never knew, never knew that I never knew!

But nested inside a box filled with snapshots and report cards, an old spiral notebook waited to be found. The cover was thick and hard, truly cardboard, the spiraled wire a tad rusted, no writing on the outside told me to whom it had belonged. When I opened the cover, however, I knew right away. My father's handwriting, slanted and artistic, yet male, even and flowing, filled page after page.

I cried. Let's get that out of the way. Every time I see my father's handwriting I grieve. He held the pen, he wrote those words. He is gone and I am left only with memories and envelopes and handwriting. Thankfully, he was an artist, and I have his paintings as well. But there's something so intimate in the handwriting of the dead, this physical remnant of their everydayness. The dead don't leave behind in any tangible way the manner in which they stirred their coffee or dragged a comb through their hair. Only in our minds do we see our mothers blot their lipstick on a kleenex or our fathers put in their cufflinks or shuffle through their wallets for a dollar bill. But handwriting sits before us in real ink on real paper, a snapshot of "their way".

Inside the notebook lay poems and thoughts of my father as a young man. He was twenty-three and the year was 1951. I found out he'd wanted to be a priest:

To raise His Body up on high

For all the world to see

To raise His Blood to cleanse the world

For sinners like me to bathe in the hopes

To console the dying and bring them peace

Underneath the garb of black

In a little gold case that holds the Life

And the key to better things.

He'd never said a thing. For in truth, in 1952 he'd met my mother, a woman with cancer. He married her believing she would die soon, that he could bring her comfort in her death.

Quickly I approached her bedside

What could have happened

The tanks, the tent, the hoarse breathing

Dear God, don't let it be.

She was in a light slumber

The void that shuns the pain

Her face was pale and drawn

Her lips drained and thin.

But she lived, recovered, and lived another fifty years. And now, perhaps, I understand my father a little bit more. A man who yearned to be in communion with God, deep communion. He wrote of love, of charity, of death, of marriage. He even wrote of the frustrations of furniture shopping with one's fiancee in a piece he titled, "On Furniture and Other Things."

"Should it be gold and brown, or coral and coco? Well, it wasn't any. It turned out coral and black. It's like the old saying, 'Did you ever have the feeling you wanted to go and still the feeling you wanted to stay?'"

Why do I write of these things? These discoveries which strip away the hard coverings of my father and reveal the young man beneath? Because in this book I found myself, that portion of me that must write life down, and I found it in a place I never knew existed. And somehow, finally, it all makes sense. Perhaps I write for different reasons than I ever thought. Perhaps I write not because I can or because I ought. Perhaps I write because I am my father's daughter, and he was just like me, but somewhere along the line (was it due to marriage, his practice, his children) he simply stopped writing things down.

That's all we do, really, isn't it? We're just writing things down. Sometimes I forget the true simplicity of what I do. But a reminder surfaced in a dirty old basement and gave me reason to keep placing pen to paper, to write of love and charity and marriage, to write of death and dreams and even furniture shopping.

To write of life, to write of God, to write of life.

Lisa Samson writes from an old house in Lexington, KY. Find her at http://www.lisasamson.com/.

9 Comments:

Touching, real. A true treasure to find as only God could've given.

I'm left speechless by your beautiful tribute.

Thank you for being your dad's daughter, Lisa. Your words are a treasure.

Oh, Lisa. So happy for your discovery....

After my dad died, 22 years ago, my mother had copies of all his poems made into little books for each of us kids. They cost her $1 each. Mine is one of my treasures.

In large part, I keep writing because somewhere along the line my father stopped writing.

Katy McKenna www.fallible.com

Lisa, you rock.

Wow. I have no such memories or souveniers, but I hope to leave something that is inspiring or valuable to my girl. Perhaps it will only be a grocery list, written in my hand, but I would want her to see my words and smile in rememberance.

Thanks, Lisa.

Beautiful.

We have that in common. My dad was an artist, too. An engineer first, he began to paint when he retired. He painted and planted churches. He had a heart for the Hispanics, yet never spoke a word of Spanish. He left a rich legacy and passed on to me the gift of faith.

Beautifully presented. Thanks for sharing your message. It touched my heart as it brought back memories the notes I found among my late wife's things. The one that brought tears to my eyes was the slip of paper I discovered the week after her funeral. It simply read, "Romans 8:38-39."

Beautiful tribute to your father and a touching account of how his legacy lives on in you.

Post a Comment

<< Home